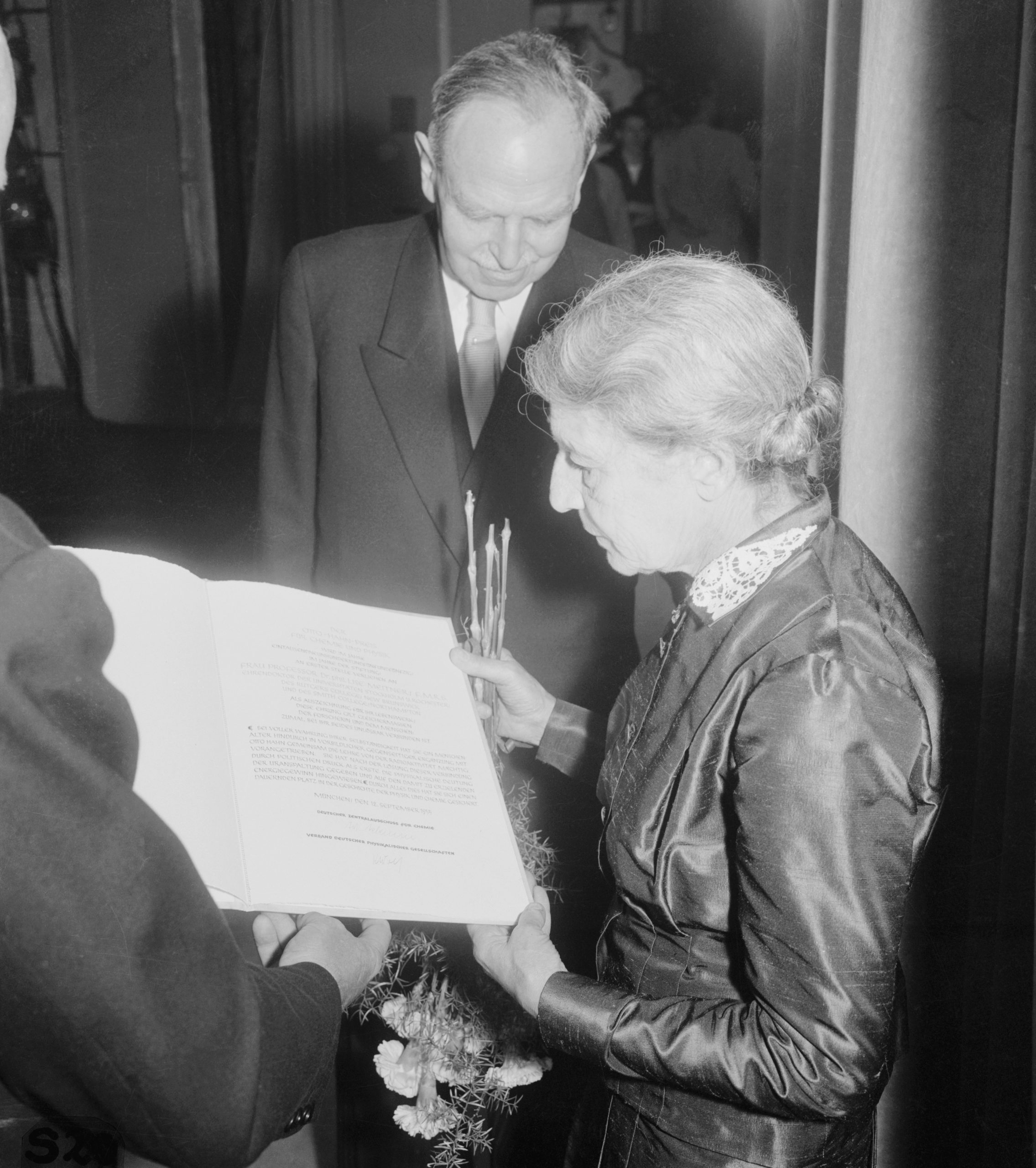

The more I study history, the more I realize how much important information never appears in most textbooks. For example, the role of women.

I’ve just stumbled across the story of Lise Meitner, who was born in Vienna, Austria in 1878. She was the second woman to receive a Ph.D. in physics at the University of Vienna. After moving to Berlin in 1907 and attending lectures by physicist Max Planck, she became his assistant. One of the people she met in that role was chemist Otto Hahn.

Meitner and Hahn proved to be a complementary match — she was analytical and he was creative — and soon they were working together, researching radioactivity at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry. They were such a productive team that colleagues nominated them 10 times for a Nobel prize.

Unfortunately, Nazi ideology still considered Meitner a Jew even though she had been baptized as a Christian. So she prudently fled to Sweden when Germany took over Austria in 1938.

Yet she continued her working relationship with Hahn, which included studying the atomic nucleus and uranium. This led to a breakthrough when Hahn broke the uranium nucleus it into smaller, separate bits. Except he didn’t know how to explain exactly why that had happened.

The explanation fell to Meitner who, along with her nephew Otto Frisch, pieced together a theoretical framework; they called the new process “nuclear fission.”

Several weeks after Hahn published his findings of their joint research in 1939 (he left out her name, knowing it would cause trouble), Meitner and Frisch published their explanation in the journal Nature. Interestingly, the word “fission” wasn’t used in Hahn’s paper, though it did appear in the announcement that Hahn (alone) had won the Nobel Prize for the breakthrough.

Despite her contributions, it became accepted that Meitner was Hahn’s junior partner. Worse, the process they discovered was also central to building the atomic bomb, with which Meitner disapproved. Although she didn’t campaign against atomic power, she did refuse to work on the Manhattan Project. Yet despite keeping her distance, Meitner still became known as “the mother of the atomic bomb.”

Although she never won a Nobel, recognition came in other ways. A few years after Hahn’s Nobel award, Meitner was given the Max Planck medal, and in 1966, the U.S. Department of Energy honored her, Hahn and his assistant Fritz Strassmann with the Enrico Fermi Award. She’s also only the second woman to have had a chemical element named after her — the highly radioactive and artificially created meitnerium (number 109).

By the way, there is no element named for Otto Hahn.

Taken from “The Brilliant Female Brain Behind the Bomb” by Dan Peleschuk (https://www.ozy.com/true-and-stories/the-brilliant-female-brain-behind-the-bomb/266475/). The photo is from that site.