History.com

When you studied slavery and the slave trade in school, how many rebellions were you taught?

On Thursday of this week, I was helping out in middle school social studies, and I learned something that just wasn’t mentioned when I was in school.

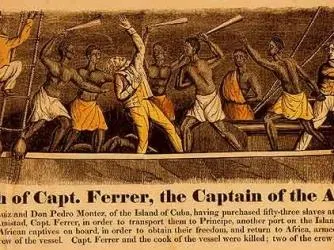

In 1839, there was a successful rebellion aboard the slave ship Amistad. Fifty-three Africans had been sold in Havana, Cuba, to work on a sugar plantation. But in transit to their final destination, they were able to break free, kill the captain and a sadistic cook, and otherwise take control of the ship.

The goal was to return to Sierra Leone in Africa. But the Amistad ended up off the coast of Long Island, where it was stopped by a U.S. Navy ship under the suspicion of piracy, and the Spanish co-owners of the slaves, who were supposed to steer them back to Africa, were set free. The slaves themselves were imprisoned in Connecticut.

What was their legal status? Were they still property? If so, who did they belong to? Or were they freemen? Here’s where the miracles start.

Miracle #1 — Despite President Martin Van Buren’s wish to return them to the Spanish, a Hartford, Connecticut judge ruled in January 1840 that they had been illegally brought to Cuba and therefore were not enslaved.

Miracle #2 — When the Van Buren administration appealed to the Supreme Court, former President John Quincy Adams was recruited to represent the Africans. His eloquence helped convince the Supreme Court to vote 7-1 to uphold the lower court’s decision in March 1841.

Miracle #3 — Despite the victory, no money was allocated for their return to Africa. Ultimately, through the efforts of abolitionists, 35 survivors of the original 53 finally set sail for Sierra Leone in late 1841.

This remarkable chapter in history galvanized the abolition movement in this country, but is mostly forgotten today. For a more complete story, read “How the Amistad Rebellion, and Its Extraordinary Trial, Unfolded” by Jesse Greenspan (https://www.history.com/news/the-amistad-slave-rebellion-175-years-ago).