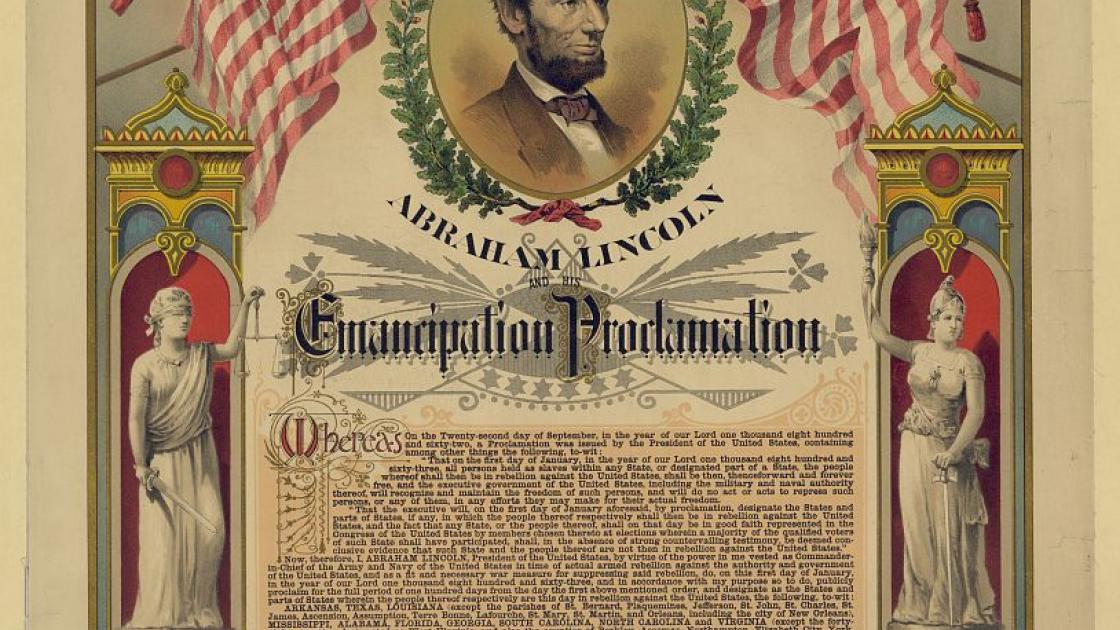

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued one of the most important documents in U.S. history — the Emancipation Proclamation, except it was preliminary. This first issuance was meant as a warning: if the Confederate states did not end their rebellion by January 1st, 1863, then his Proclamation would take effect for real. Unfortunately, the rebellion continued, so the Proclamation was formally issued with the coming of the new year, which meant it was actually issued twice.

It is important to remember that the Proclamation didn’t apply to all slaves, just those who lived in the rebelling states. Lincoln couldn’t afford to alienate the border states, Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland, who had not joined the Confederacy and were critical to the war effort (especially since Washington D.C. was actually in the South).

Issuing the Proclamation had several important effects —

First, it altered the focus of the war. Up until that time, the main goal had been to preserve the Union. Now freeing the slaves became a major objective.

Second, by focusing on slavery, European nations like Great Britain and France were more reluctant to support the Confederacy. Normally there is a great temptation to pick a side in a civil war to expand influence and even weaken a rival, like France entering the American Revolution on the side of the rebels. But Europeans had little sympathy for slavery. This, coupled with the Union victory at Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland on September 17, gave Europeans pause — why intervene if the Confederacy wasn’t winning? (Compare this with the colonists’ victory at the Battle of Saratoga in the Revolutionary War, which convinced France that a British victory was not inevitable.)

Third, African Americans could now legitimately join the war effort. The War Department’s General Orders No. 143 establishing the United States Colored Troops (USCT) was issued five months later. Ultimately, more than 200,000 African-Americans would serve in the Union army and navy.

So why did Lincoln wait until September, 1862 to mention the Proclamation? Waiting kept the focus of the war on preserving the Union, his cabinet wasn’t fully supportive, and there wasn’t much point in pontificating about slavery if the North couldn’t win. But stopping the Confederate invasion at the Battle of Antietam, which many historians call a draw, gave Lincoln the opening he needed.

And yet, by promising to free slaves only in the rebelling states, Lincoln betrayed moral principle for political reality. As Secretary of State William Seward saw it, “We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free.”

For more information, see “10 Facts: The Emancipation Proclamation” (https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/10-facts-emancipation-proclamation) and The Writer’s Almanac for September 22, 2020 (https://www.spreaker.com/show/the-writers-almanac?)