People simply don’t like change. When I was in the publishing business, the company I had just joined had the opportunity to expand. There was a casket-supply company close by whose business was (if you’ll pardon the expression) dying, so we had a chance to move into their location. Yet some neighbors were very vocally against it, and we ended up seeking other options. They couldn’t seem to comprehend that we were not bringing in a threat to their neighborhood.

This NIMBY (not in my backyard) attitude is certainly true regarding energy sources. It seems no one wants a solar-energy farm or a cluster of windmills located next to their property.

The sad fact, as we transition to renewable energy, is opposition to change is nothing new, as an article in the July-August issue of Smithsonian Magazine reminded me. “When Coal First Arrived, Americans Said ‘No Thanks’” by Clive Thompson (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/americans-hated-coal-180980342/), relates how the transition from wood heat to coal was surprisingly contentious.

Until the early 1800s, wood was plentiful and cheap. But as the country grew, people gradually realized wood supplies were becoming scarce and more expensive. On top of that, fireplaces were terribly inefficient — most of the heat was lost up the chimney.

Fortunately, the young nation was blessed with huge deposits of coal. Yet convincing households to switch fuels was much harder than one would think.

First, coal burns hotter, too hot for fireplaces; a metal stove would be required. These were both expensive and rare. Plus, they didn’t provide the comforting view of an open flame. In fact, some considered them downright un-American. In a 1843 short story Fire Worship, writer Nathaniel Hawthorne claimed that gathering at a flickering hearth was crucial to bringing families together. “Social intercourse cannot long continue what it has been, now that we have subtracted from it so important…an element as firelight. While a man was true to the fireside, so long would he be true to country and law.”

Also, food cooked in a metal stove was baked, not broiled, and that required a cultural adjustment. The smell was less pleasant and coal (especially softer varieties) produced sooty air. It got to the point where stoves were suspected of causing all manner of ills. “People were blaming coal-fired stoves for impaired vision, impaired nerves, baldness and tooth decay,” says Barbara Freese, author of Coal: A Human History.

Perhaps the topper was people found coal fires much more difficult to light. One period analysis found new stoves actually added an hour of work to a housewife’s chores.

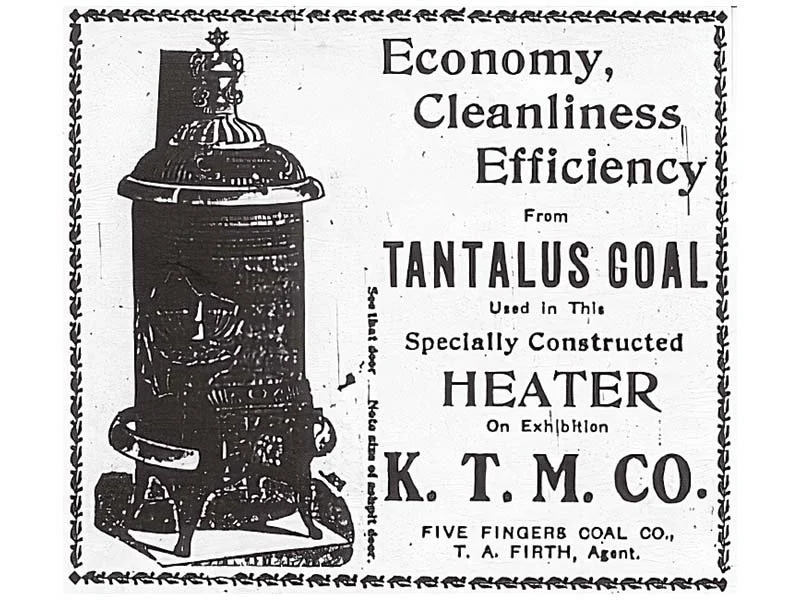

It took an all-out marketing campaign from the mining and railroad companies before coal was accepted in households. There were practical demonstrations in hotels and testimonials from the wealthy. State governments helped by conducting surveys to identify the yield of coal fields to build investor confidence. To make fuel and stoves more affordable, coal companies bought in bulk during the summer, when prices were low, to sell to poor families in winter, and even lent them metal stoves.

Finally, the stove technology improved, becoming easier to maintain, and they became more aesthetic. “They’d put busts of George Washington on top of the stove and stuff like that, so that you could have it in your parlor,” says Sean Adams, a professor of history at the University of Florida and author of Home Fires: How Americans Kept Warm in the 19th Century. As a result, most households were making the switch by the 1860s.

So this cautionary tale is something to keep in mind the next time you see solar panels being installed in your neighborhood.